Which of These Is a Style in Art History

4.four: STYLES OF ART

- Page ID

- 10132

In addition to looking at where along the spectrum from representation to non-representation a piece of work of art may autumn, nosotros can examine the way of the work. Way can encompass the principles almost course and appearance shared within a sure culture or era. Manner can refer to a movement or group of artists and their piece of work, where the commonalities can range from employing like elements and principles of design, to using certain materials or processes, to following a set of religious, political, or ideological beliefs. Style besides indicates the visual characteristics of an individual artist's piece of work. Nosotros comport a stylistic analysis past examining the creative elements and because how they have used, and how they relate to other works by that creative person, group of artists, or in a certain time frame, civilisation, or region.

In general, artistic styles tend to fall into 3 wide categories: Period, Regional, and For- mal styles. Period styles are groups of art in which the works derive their characteristic construction from the culture prevalent during a particular time flow. A skilful example of a period mode would exist Gothic Art or Ming dynasty Art. Regional styles are groups of art in which the works derive their structure from the culture prevalent in a detail place. A good example of a regional manner would be Dutch Art or Latin American Art. Formal styles are groups of art in which the works derive their structure from principles that are not characteristic of either one place or one time. A adept instance of a Formal mode would be Surrealism, Impressionism, or Modernism. Formal styles tend to exist the "isms."

From the earliest times, we tin can see that some artists sought to brand their depictions conform closely to what they saw in the earth around them, but that for various reasons they ofttimes chose to emphasize certain aspects at the expense of groovy naturalism. It is a fault, even so, to assume that the degree of naturalism that you meet in the artwork is necessarily and primarily related to the skill level of the creative person.

Creative and stylistic change is generally a thing of evolution, and oftentimes rather reactionary. The artistic choices well-nigh style (and other matters) made at whatsoever particular point are influenced by what other works of fine art look like at that moment. So the artist volition likely endeavour to create an expression that goes further in one direction, or changes directions in some way. Thus, fine art might become more naturalistic, equally nosotros have seen, or it might become less and then, because the artist thinks the fine art might express the idea meliorate past using a slightly different style or a radically unlike idea. The difference is related to electric current "thinking" within the civilization and other more specific circumstances.

4.4.1 Cultural Style

There are artistic choices with regard to way in every piece of work. While these choices are generally made at the discretion of the individual artist today, for much of history way has been a reflection of the broader cultural currents that influence so much of life in any time and place. These cultural factors have oftentimes led to the general approaches to representation that art historians telephone call "conventions of representation." To acquaint ourselves with these conventions and how they pertain to a cultural style, we will look at a few examples.

iv.4.one.1 Ancient Near East

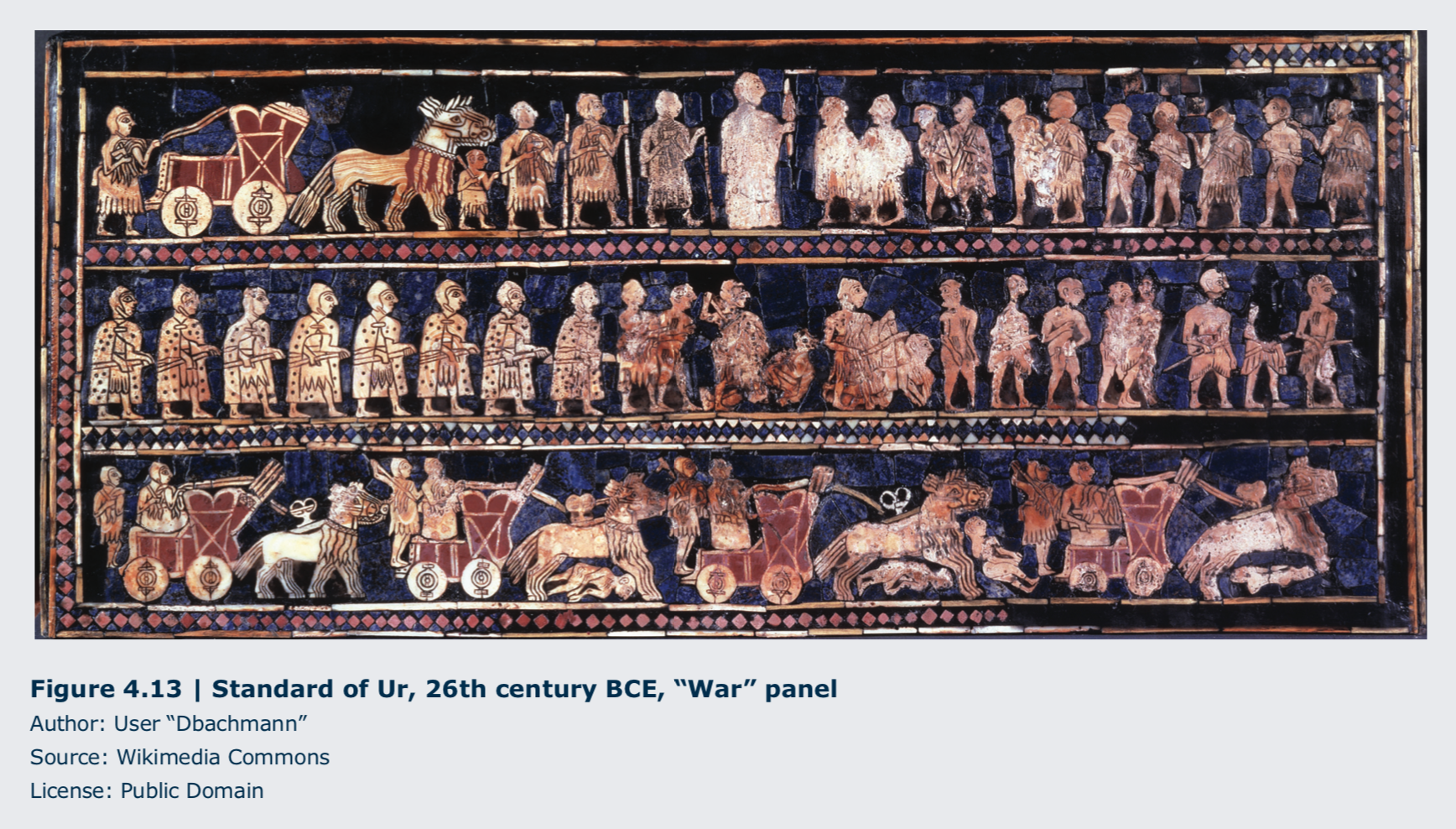

These conventions are evident to u.s.a. when nosotros examine a broad selection of works from those created in the ancient Near Eastern cultures during several centuries. Look at the way figures are depicted in a detail from the Standard of Ur (c. 2600-2400 BCE) from aboriginal Mesopotamia, to- mean solar day Iraq, a wooden box with scenes of state of war and peace made from inlaid pieces of iridescent shell, ruby-red limestone, and blue lapus lazuli. (Effigy 4.xiii) Nosotros see the figures accept sufficient naturalism to let us to hands recognize the human body. But we also meet that they include a range of natural- istic detail.

The figures announced static, even when they are shown to be moving through infinite. They are shown in a blended view, that is, with portions of the body shown in profile and others in frontal view so the creative person can provide details that would non exist visible in a strict profile. They turn the body in space so that the viewer sees the hips and shoulders, along with a twisted torso, turned slightly towards the viewer. For warriors and leaders, this is a heroic stance, showing power and command. The composite view is completed by giving a frontal view of the heart on the profile of the face up and head shown.

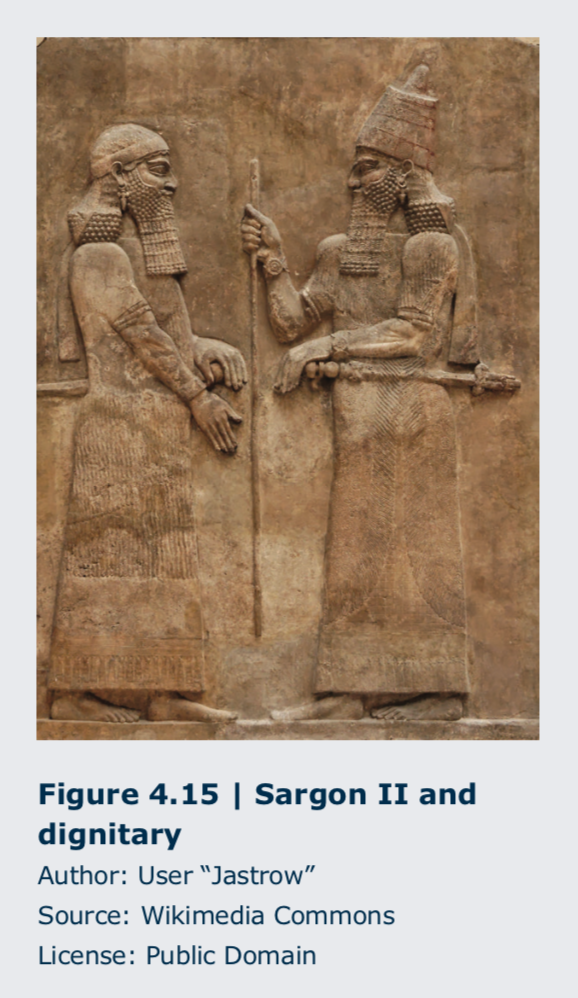

This approach to figural forms continues in addition- al ancient Almost Eastern works. The Stele of Music (c. 2120 BCE), depicting Gudea with attendants in 1 register and musicians below, shows the king ceremonially preparing to lay out a temple in the city of Girsu while accompanied by music and chanting. (Figure iv.14) In the relief of Sargon II, an Assyrian king who ruled 722-705 BCE, created approximately 1,400 years later, we see the utilise of these devices once again, forth with more variations of costume and headgear. (Effigy 4.15)

This approach to figural forms continues in addition- al ancient Almost Eastern works. The Stele of Music (c. 2120 BCE), depicting Gudea with attendants in 1 register and musicians below, shows the king ceremonially preparing to lay out a temple in the city of Girsu while accompanied by music and chanting. (Figure iv.14) In the relief of Sargon II, an Assyrian king who ruled 722-705 BCE, created approximately 1,400 years later, we see the utilise of these devices once again, forth with more variations of costume and headgear. (Effigy 4.15)

These instances drawn from beyond many centuries but from the same geographical region that is today Republic of iraq, show the persistence of a gear up of conventions of representation shared past the related cultural groups. We tin also observe hither that, when there is more emphasis on naturalism of the human body, it is at the service of carrying a sense of power, usually to give more detail to musculature especially in the breast and shoulders. This slight abstraction or deviation from absolute naturalism is also used to create a sense of greater physical stature and presence, a manipulation of actual sizes known as hierarchical proportion, meant to show the fig- ures' relative importance. These conventions of representation serve to convey dignity and significance within the wide cultural style shared by these associated groups.

As noted, abstraction is not a mod method of art, just has been used purposefully in many eras. Abstraction, simplification of naturalistic forms, appears in the conventions of representation in the ancient Near East; dissimilar almost later instances of abstraction, however, these conventions did not follow up on and prove a reactionary counter movement to a naturalistic approach, nor were they a phase that further amplified sure features for purposes of expression or emotional exaggeration.

As noted, abstraction is not a mod method of art, just has been used purposefully in many eras. Abstraction, simplification of naturalistic forms, appears in the conventions of representation in the ancient Near East; dissimilar almost later instances of abstraction, however, these conventions did not follow up on and prove a reactionary counter movement to a naturalistic approach, nor were they a phase that further amplified sure features for purposes of expression or emotional exaggeration.

iv.5.1.2 Ancient Greece and Rome

We before discussed the progression of cultural style in ancient Hellenic republic from the Primitive period to the High Classical catamenia. The latter was likewise the era when the Parthenon temple and the other structures on the Acropolis in Athens were rebuilt or renovated as a statement of the power of that urban center-country. (Figure 4.16) The piece of work of this era of artistic acme is called classical.

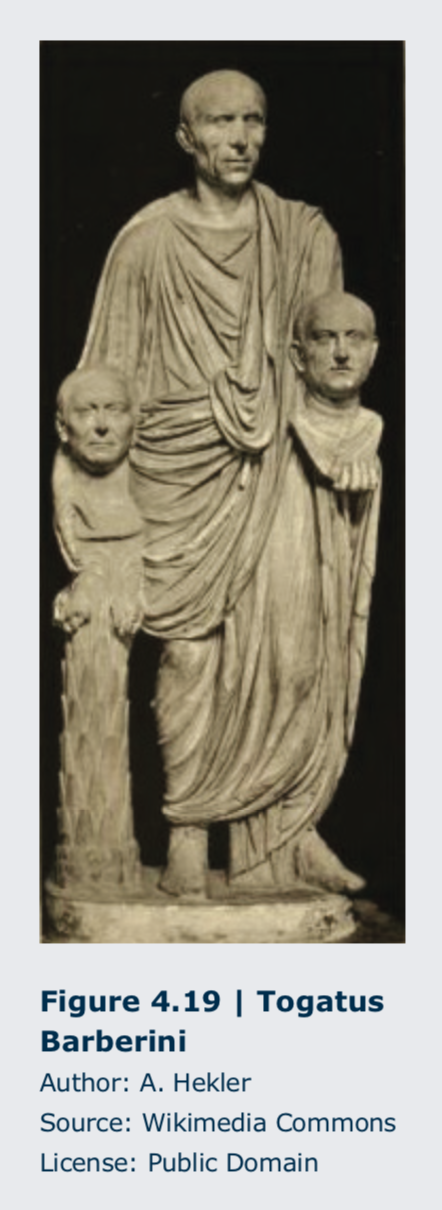

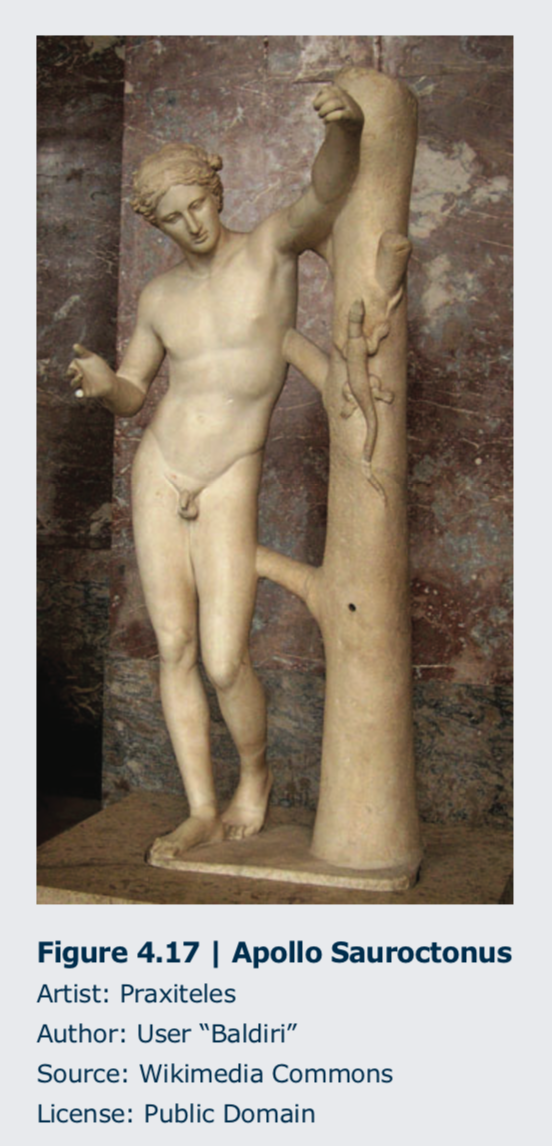

By extension, the aboriginal Roman work that was created to emulate the Greek Classical style is sometimes defined, also, every bit classical art. Conscientious distinctions, though, demand to be made amongst the strictly classical, the imitative, and the revival of classical form in later eras. Examining these styles further, let us get-go look at what happened afterward the Greek High Classical era. Art in Greece, in what are called the Late Classical (400-323 BCE) and Helle- nistic (323-31 BCE) periods, shows changes that move away from the Loftier Classical norms in becoming variously more dynamic, more than expressive, more emotional, more dramatic. (Figures four.17 and four.eighteen) That is, they are exaggerated in some way from the calm composure of the Classical way that had expressed the cultural value of complete residuum achieved by "a sound mind in a sound body," a rather sober and self-independent platonic.

In later Greek civilization, nosotros can come across changes in an expansive political spirit, the influx of foreign cultural forces, the development of drama in theater, increasing materialism, and other factors that change the creative and aesthetic spirit, consequently requiring different modes of creative expression. The Romans, although deeply admiring the classical Greek art, held unlike cultural ideas and ideals, so Roman fine art, unless direct copying the Greek, would express their different views of life and the earth. These included particularly Roman worldliness, their boundless interest in expansion (which brought in a great variety of additional influences), their nifty ingenuity and creativity in such arenas as technology and architecture, and their stress on individualism.

The Roman Republican period (509-27 BCE) overlaps the Greek late Archaic, Classical, and Hellenistic periods. During the Republican period, Romans favored an anti-arcadian approach to portrayal of people that went beyond elementary naturalism to a very frank and unvarnished report of individuals, with a measure of veneration for the more than mature citizens as models of an accomplished life.(Figure 4.xix) The Romans honored their ancestors and kept their venerable images as portrait heads, which they carried in funeral processions and kept in their homes; they valued the accomplishments of old age, so their views on aging and the aged were often expressed through veristic or truthful renditions of their likenesses.

However, the utilize of these unidealized depictions varied from one phase to some other throughout ancient Roman history. It is especially noted that in the Early Majestic era (27 BCE-197 CE), with the rise of Augustus to Emperor, the practice of idealization in portraiture was once more favored for the purple likenesses, frequently seen clearly equally part of the political propaganda used to promote the positive perception of the emperor and the promotion of his political goals and programs. The portrayal of the man Augustus, regardless of his age at the time of the cosmos of a portrait, was fabricated to be the image of a powerful young man, heroic in stature, fit and fine. (Effigy 4.twenty) Ensuing emperors varied their choices in this regard, some opting for a return to the age prior to the Imperial Age and notions of Republican virtue and the value of historic period and experience, others using the idealizing and propagandistic arroyo, to some degree.

In the late Roman Empire (284-476 CE), though, nosotros see suppression and streamlining of natural detail in art that followed and was a reaction to that long period of naturalistic representations of the human figure. Scholars interpret this brainchild equally a ways of stressing other-than-natural features that are ideological, spiritual, or philosophical in graphic symbol. For example, in the Portrait of the Four Tetrarchs from c. 300 CE, we run into that the idea of the tetrarchs, or four co-ruling emperors, working together to rule the four divisions of the vast Roman Empire is more important than the representation of likeness of any one of these co-rulers as an individual. (Figure four.21)

Naturalism has given manner to uniformity, with nearly identical figures of men in the aforementioned costume, crown, armor, and stance, every bit they cover one another to evidence their joint function and efforts in the service of the Roman denizens. Even though there is considerable detail in their clothing that links their joint rule to Roman traditions of military rulers and leaders, the suppression of distinctive, private physical characteristics is used convey the concept of how they will function every bit one.

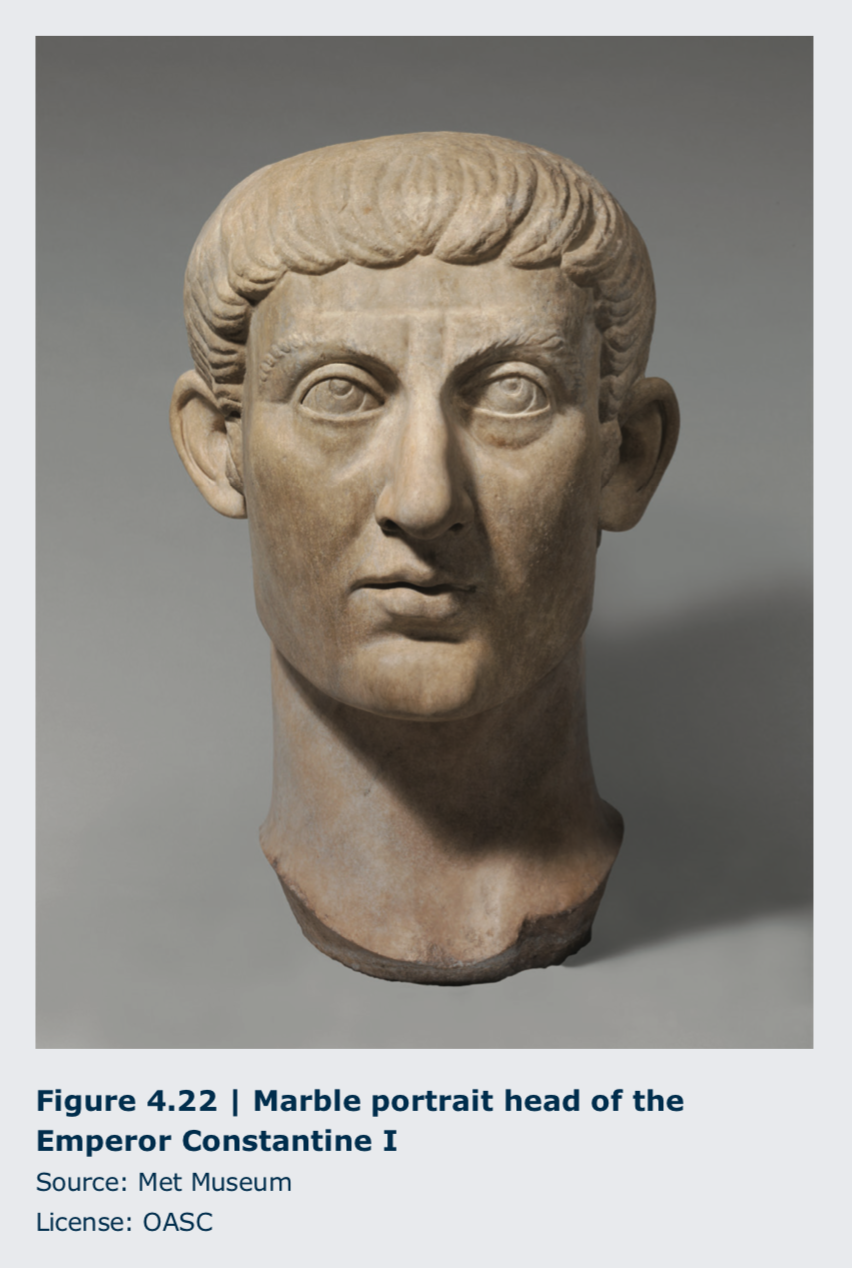

A few years afterwards, when the Roman Empire briefly re- turned to a singular rule under Constantine the Not bad, the new Emperor opted for an even more abstracted and simplified portrait representation. (Figure four.22) He thus removed himself even further from the tradition of imperial portraits that had each varied in its extent of naturalism and idealization even though the caput emulates some in being clean-shaven, with a fringed cap of hair, and having an air of imperial hauteur. Simply it is far less personal and less intimate in its address to the viewer, both in large part to its marked suppression of detail, than depictions of earlier rulers. Farther, Constantine appears to exist focused on the heavens above, towards which his gaze is directed. The portrayal has been read as existence more spiritual, linking him to the emerging Christian faith. Thus, the portrait is associated with a societal and cultural turn from worldly to spiritual matters, and that is probable reflected in this modify in artistic interpretation.

4.4.1.iii Indian Subcontinent

Strictly speaking, Greece and Rome were the classical civilizations of antiquity in the W, and some would even limit the utilise of the term "classical" in fine art to the High Classical menses in Hellenic republic. The same principles and conventions of representation, however, include numerous works from other times and places. The revival of characteristics associated with the cultural styles associated with ancient Greece and Rome recur repeatedly throughout history in the Due west, and also announced sometimes in not-Western cultures. Condign familiar with a few examples will make more apparent the variations of a naturalistic fashion, whether subtle or quite pronounced, that can be further investigated with regard for the cultural and individual values that are influential at the moment of the work's creation and utilise.

In India, naturalism was not unremarkably as restrained as those of the classical ideal we have been exploring. The Emperor Ashoka (r. 268-232 BCE), who reigned over most of the Indian sub- continent, oversaw the construction of 84,000 stupas, dome-shaped shrines, to house Buddhist relics. In this Yakshi, or female person nature effigy, guarding one of the fours gate at the Great Stupa at Sanchi, the emphasis is on fleshy class, voluptuous and prosperous, indicating a robust healthy physique with connotations of earthly approval and prosperity. (Figure 4.23)

During Ashoka's reign and in the succeeding centuries, influenced by increasing contact with Western cultures and creative styles that came with both friendly trade and aggressive armed services incursions by Greeks and Romans, many changes occurred in Indian art. A notable case is the Buddhist sculpture of Maitreya from Gandhara (today Pakistan), dating to the tertiary or fourth century CE. (Effigy 4.24) Maitreya, de- rived from the Sanskrit word for "friend," is a bodhisattva—a person who is able to reach nirvana but compassionately chooses to help others out of their human suffering. Maitreya, a successor to the current Buddha, volition announced in the future.

During Ashoka's reign and in the succeeding centuries, influenced by increasing contact with Western cultures and creative styles that came with both friendly trade and aggressive armed services incursions by Greeks and Romans, many changes occurred in Indian art. A notable case is the Buddhist sculpture of Maitreya from Gandhara (today Pakistan), dating to the tertiary or fourth century CE. (Effigy 4.24) Maitreya, de- rived from the Sanskrit word for "friend," is a bodhisattva—a person who is able to reach nirvana but compassionately chooses to help others out of their human suffering. Maitreya, a successor to the current Buddha, volition announced in the future.

The influence of Greek and Roman art can be seen in the treatment of drapery and the concrete class. Although the figure is somewhat fleshier than Western counterparts, retaining the Indian penchant for more total-bodied physique, it is somewhat less substantial and certainly more concealed by the envelopment of abundant cloth than what had earlier been the norm for figural interpretation in Republic of india.

4.4.one.iv Romanesque and Gothic Eras in Europe

Returning to Europe, Romanesque art of the eleventh and 12th centuries is noteworthy with regard to the thought of expressing a prevalent preoccupation amongst Christians about the ends of their lives and the end of fourth dimension. For spiritual purposes, they often made a choice for greater brainchild and baloney, rather than the emphasis on a naturalistic depiction of the human form as seen in ancient Greek and Roman art. Their forms are not simply simplified with suppression of naturalistic features in some ways, just are too twisted and turned in space, while their garments take a lot of linear detail that does non correspond well to the physical forms of the bodies they beautify. The issue is to remove their significant from a focus on worldly phenomena, redirecting information technology to a sense of spiritual agitation.

Many of the depicted scenes re- late to the Christian expectations of the event of the Concluding Judgment, reflecting warnings to the devout that that their lives and deeds now will be assessed at that bespeak in the future. At Autun Cathedral (1120-1132) in France, we come across a graphic array of elongated figures in the Last Judgment within the tympanum, the space above the portals, or doors. (Figure iv.25) The scene and surrounding decorative reliefs, created by the sculptor Gislebertus (active c. 1115-c. 1135, France) between 1130 and 1135, are centered on the flattened figure of the judging Christ. He presides over the resurrection of the dead and the ensuing assignment to a heavenly welcome or a grotesque greeting by the denizens of Hell. Despite the lack of naturalism, the letters are articulate in reference to human feel and prevalent beliefs of the era.

Following the Romanesque style in Europe was the Gothic era, which spanned the twelfth to fourteenth centuries in Italy and continued into the sixteenth century in northern Europe. The Gothic style included a return to greater naturalism, as focus shifted back to the natural globe in many means. (Figure 4.26) Figural forms began to reflect the observation of physical facts, and a phase of artistic development began that would eventually culminate in the intense naturalism of the Renaissance, especially in Italia from the fourteenth to the sixteenth centuries.

Following the Romanesque style in Europe was the Gothic era, which spanned the twelfth to fourteenth centuries in Italy and continued into the sixteenth century in northern Europe. The Gothic style included a return to greater naturalism, as focus shifted back to the natural globe in many means. (Figure 4.26) Figural forms began to reflect the observation of physical facts, and a phase of artistic development began that would eventually culminate in the intense naturalism of the Renaissance, especially in Italia from the fourteenth to the sixteenth centuries.

Along the mode, however, conventions of representation in Italy and in northern Europe diverged, producing increasing different cultural styles. For example, the "Court Mode" was prevalent in the royal works of the Belatedly Gothic era (late fourteenth to sixteenth centuries), particularly in France, and lingered into the early Renaissance of the tardily fifteenth century in northern Europe. The approach reflected the prominence of aristocratic tastes and the exaltation of earthly rulers and the formulation of God and the saints (especially the Virgin Mary) as the courtroom in Heaven. (The Virgin of Paris, Notre-Dame, Paris: https://world wide web.oneonta.edu/ faculty/farberas/arth/Images/arth212images/gothic/notre_dame_madonna_child.jpg)

While there is a clear alter from the Romanesque style, the figures are not still really naturalistic, with an emphasis on elegance and aristocratic attitude dominating the figural imaginings. Equally seen here, there is often arable pall falling in rich and graceful folds, so exaggerated that one cannot discern the infinite for a total effigy below. The hips and knees, rather than showing the classical contrapposto positioning that the ancient Greeks developed, are gracefully swayed into an Due south-curve, connoting composure and refinement.

4.4.2 Stylistic Periods or Movements

In improver to examining style as a broad expression and embodiment of cultural beliefs and values, we tin focus more finely upon stylistic groups and creative movements as artists and works grouped together due to similarities in subject matter, formal approach, spiritual or political behavior, or other commonalities. A stylistic movement tin be based upon a pointed and conscientious revival of visual and philosophical traits of an earlier way. An creative movement can besides reverberate the cyclical and recurrent development of style, with phases of moving gradually towards greater naturalism, and then rebounding towards some stylistic abnormality that is less reflective of physical nature and instead expresses some other interest of human life and artistic attention.

iv.iv.2.1 Italian Renaissance

The first artistic era in the mod West that we tin speak of as possessing more than specific traits and commonalities than a more broadly divers cultural manner is the period known as the Renaissance, which is French for "rebirth." Originating in Italian republic in the fourteenth century, the Renaissance was a catamenia of witting and purposeful revival of the ideas and ideals of the classical by. Within a shared cultural interest in humanism, the philosophical belief in the value of humans and their endeavors, artists of the Italian Renaissance sought ways to limited themselves every bit individuals in their art. Through study of ancient art and shut observation of the globe around them, Renaissance artists as a group—but each characterized past singular traits—realized another pinnacle of natural- ism in the human form. Italian artists of the fifteenth century would also invent linear perspective, so that all lines parallel to the viewer'south eye recede to a vanishing point on the horizon line.

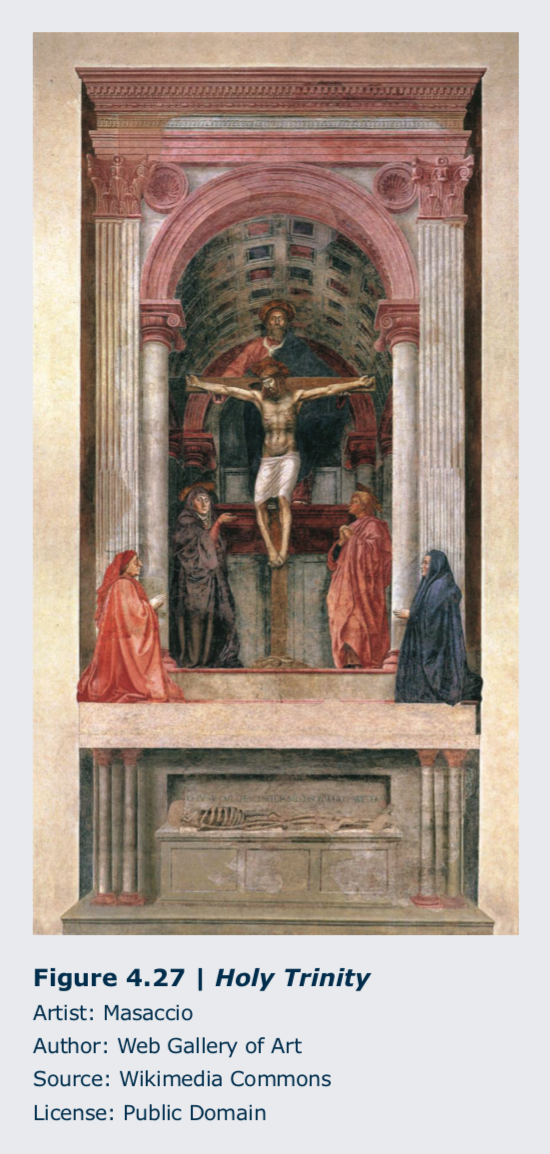

A practiced example of linear perspective is the fresco The Holy Trinity past Masaccio (1401-1428, Italy), the first painting in which the technique was systematically employed. (Figure 4.27) The work depicts the crucifixion of Christ, with God the Father behind and above him supporting the cross, and Mary and St. John the Baptist standing to either side. When we extend the orthogonal lines from the ceiling vault above the holy figures, we discover they converge at a signal on the floor where the images of the patrons kneel, below and outside the vaulted area. This line divides the fresco into two zones: the zone to a higher place that, which for Christians symbolized eternal life, and the skeleton beneath the line which symbolizes the waiting grave. The vanishing betoken and the attention of the viewer is on the line betwixt them where the patrons kneel in prayer. It thus subtly simply elegantly uses linear perspective to impart a message. The patrons and the viewer are "on the line between life and death" and have a religious determination to make.

A practiced example of linear perspective is the fresco The Holy Trinity past Masaccio (1401-1428, Italy), the first painting in which the technique was systematically employed. (Figure 4.27) The work depicts the crucifixion of Christ, with God the Father behind and above him supporting the cross, and Mary and St. John the Baptist standing to either side. When we extend the orthogonal lines from the ceiling vault above the holy figures, we discover they converge at a signal on the floor where the images of the patrons kneel, below and outside the vaulted area. This line divides the fresco into two zones: the zone to a higher place that, which for Christians symbolized eternal life, and the skeleton beneath the line which symbolizes the waiting grave. The vanishing betoken and the attention of the viewer is on the line betwixt them where the patrons kneel in prayer. It thus subtly simply elegantly uses linear perspective to impart a message. The patrons and the viewer are "on the line between life and death" and have a religious determination to make.

During the preceding Romanesque and Gothic eras, philosophical idea was shifting from a focus on achieving everlasting life through devotion and considering humans and their feats to be weak and insignificant; still, the power of faith and religious beliefs had not diminished. Humanism of the Italian Renaissance both celebrated hu- man intellectual and creative accomplishments as can exist seen in employ of linear perspective in The Holy Trinity and embraced the teachings of the Roman Catholic Church that emphasized the humanity of Christ.

Equally a result, there was a shift away from distinct physical and emotional separation of holy figures within works of art to depictions that emphasized their spiritual presence among the true-blue. For case, in the Madonna and Child Enthroned with Saints by Raphael (1498-1520, Italy), a hierarchy of Mary as the Queen of Heaven seated high on her throne with a formalism canopy and hanging cloth emphasizing her majesty is maintained. (Figure 4.28) The steps before her, however, are open up for the viewer to symbolically ascend through devotion, and the serene landscape behind her is clearly on this earth and not a vision of a angelic sky.

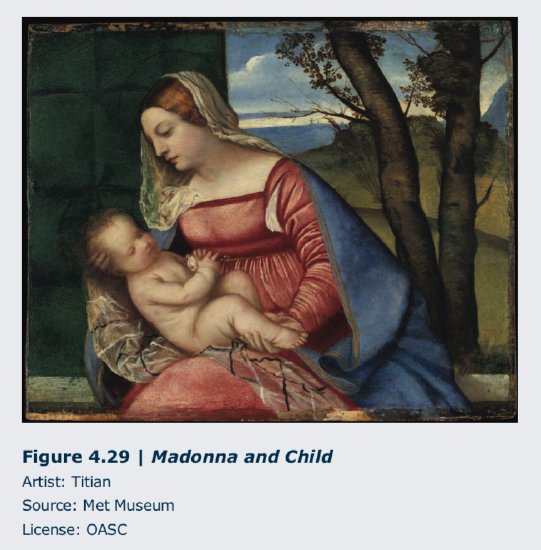

Subjects such equally the Madonna and Child, which allowed the creative person to accentuate human qualities such as the love, mercy, and tenderness which these holy figures had in common with the worship- per, were favored during the Italian Renaissance. Not only did the choice of subject affair reflect the new value placed on human being empathy and bureau, the myriad approaches to such subjects indicate the new freedom artists felt to carelessness a broad cultural fashion every bit seen in earlier eras. Instead, they adopted stylistic traits that embodied a collective want to "rebirth" the forms and philosophy of art as expert in Classical Greece and Rome. This resulted in artists accentuating the private in their art making inside the agreed upon stylistic standards and ideals of the period.

As an example, compare Raphael's Madonna and Child Enthroned with Saints to Madonna and Kid painted approximately six years later by Titian (c. 1488-1576, Italy). (Figure four.29) Both artists stress the tender connexion between mother and child. Looking closely at the faces of all three women in Raphael's work, however, nosotros can come across their features and the tilt of their heads are well-nigh identical, suggesting the artist chose to draw them in a similarly idealized mode. The Madonna in Titian'southward work, on the other hand, has more individualized facial features. Titian places a greater emphasis on the naturalistic folds and menses of mantle than Raphael does, highlighting the transparency of fabric beyond Mary's lap, for example. Last, Titian brings the detailed mural behind the figures closer to the movie plane, situating the figures in nature; Raphael focuses upon the group of figures in the foreground with a afar view of the land. In this way through their art, we take a front row seat to a irresolute cultural view about the proper relation of religious figures to the everyday concrete world during the Italian Renaissance.

four.four.2.2 Realism

We have already discussed naturalism as an approach to depicting objects that exist in the physical world in representational art. At present let us examine the terms naturalistic and realistic. These terms are oft (incorrectly) used interchangeably, simply their meanings and implications in fine art differ. Works that are naturalistic are those in which the advent corresponds to nature, that is, to how the bailiwick of the piece of work looks in the natural, phenomenal globe, such every bit the cows of Rosa Bonheur. In stardom, those that are correctly called realistic relay information or opinions virtually the underlying social or philosophical reality of the bailiwick matter: they go across the natural advent to express additional ideas.

Works created with a view to such existent- ism may also be naturalistic in advent, but they go beyond the naturalistic advent to include social commentary in the pictorial message. Examples include works such every bit those by Gustave Courbet (1819- 1877, French republic, Switzerland) that were created to express the realities of the rural poor in mid nineteenth century France and that were partly artistic statements of rebellion against the prevailing norms of academically acceptable fine art. The École des Beaux Arts was the nationally institutionalized body in control of training and exhibition of art in France, and its conservative tendencies went confronting such frank handling of mundane subject thing. Rather, they promoted lofty subject matter, refined treatments, and their most highly prized works dealt with topics like history, religion, heroic narratives, and the like. Here, in the Burial at Ornans, Courbet presented not a grand ceremonial event, but an ordinary country funeral. (Effigy four.30) The scene includes a disparate grouping of common folk continuing awkwardly in disarray fifty-fifty though the m size was associated with a more than elevated field of study and treatment.

The academic norms would have dictated that such a ritual outcome be presented with a greater sense of formality and pomp, emphasizing the coordination of activities in an uplifting and reverential manner. Since Courbet had trained and accomplished mastery in the official French system, the painting was shown in the almanac Salon, the official venue of the École des Beaux-Arts; however, it was widely criticized as lacking decorum and having besides much realism.

The academic norms would have dictated that such a ritual outcome be presented with a greater sense of formality and pomp, emphasizing the coordination of activities in an uplifting and reverential manner. Since Courbet had trained and accomplished mastery in the official French system, the painting was shown in the almanac Salon, the official venue of the École des Beaux-Arts; however, it was widely criticized as lacking decorum and having besides much realism.

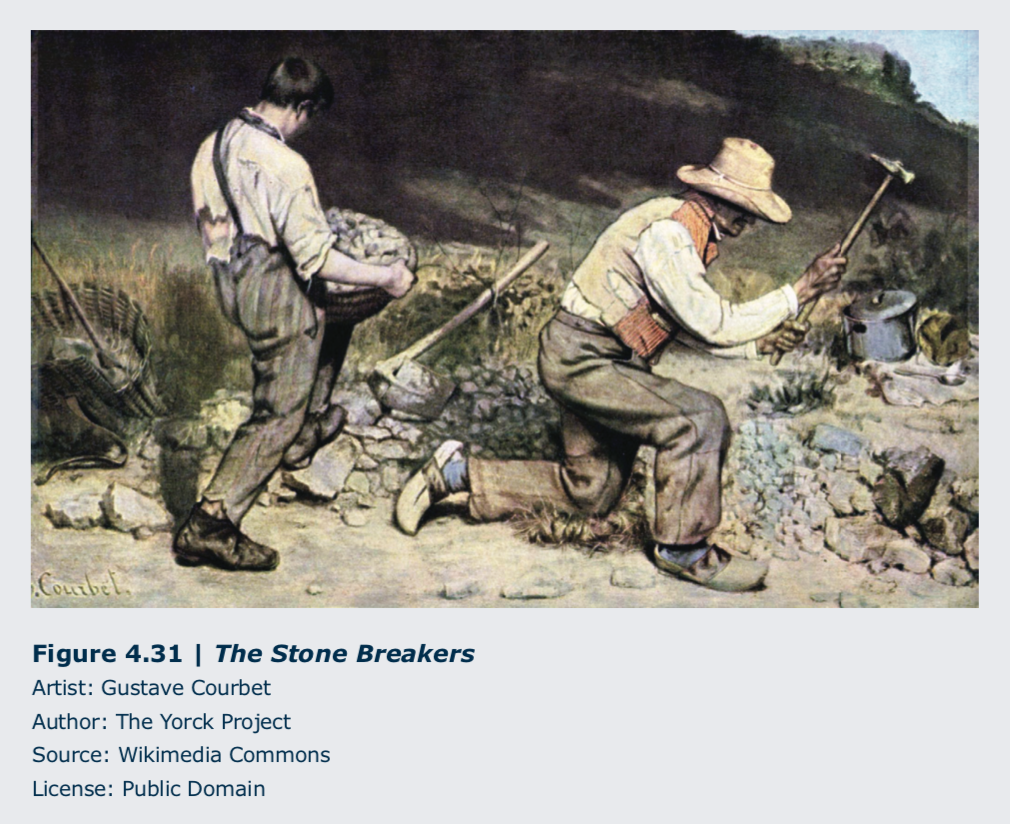

Some other of Courbet's works, The Stone Breakers, likewise shown at the Salon in 1851, garnered its share of the aforementioned sort of criticism, for information technology presented the hard labor of rural peasants as though it were a heroic activity. (Figure four.31) Courbet once again used realism to make a strong visual statement of the nobility of people and tasks that lay far exterior the refined academic definitions of art. By doing so, he condemned not simply the Academy but besides the societal standards that supported such judgment and ranking of art and human activity. Thus, the art movement known as Realism was begun. Many works created in this vein were condemned and refused for exhibition in the official Salons, resulting in an anti-Academic motion among artists and the quest of many for independence from the state controlled system for training and exhibition.

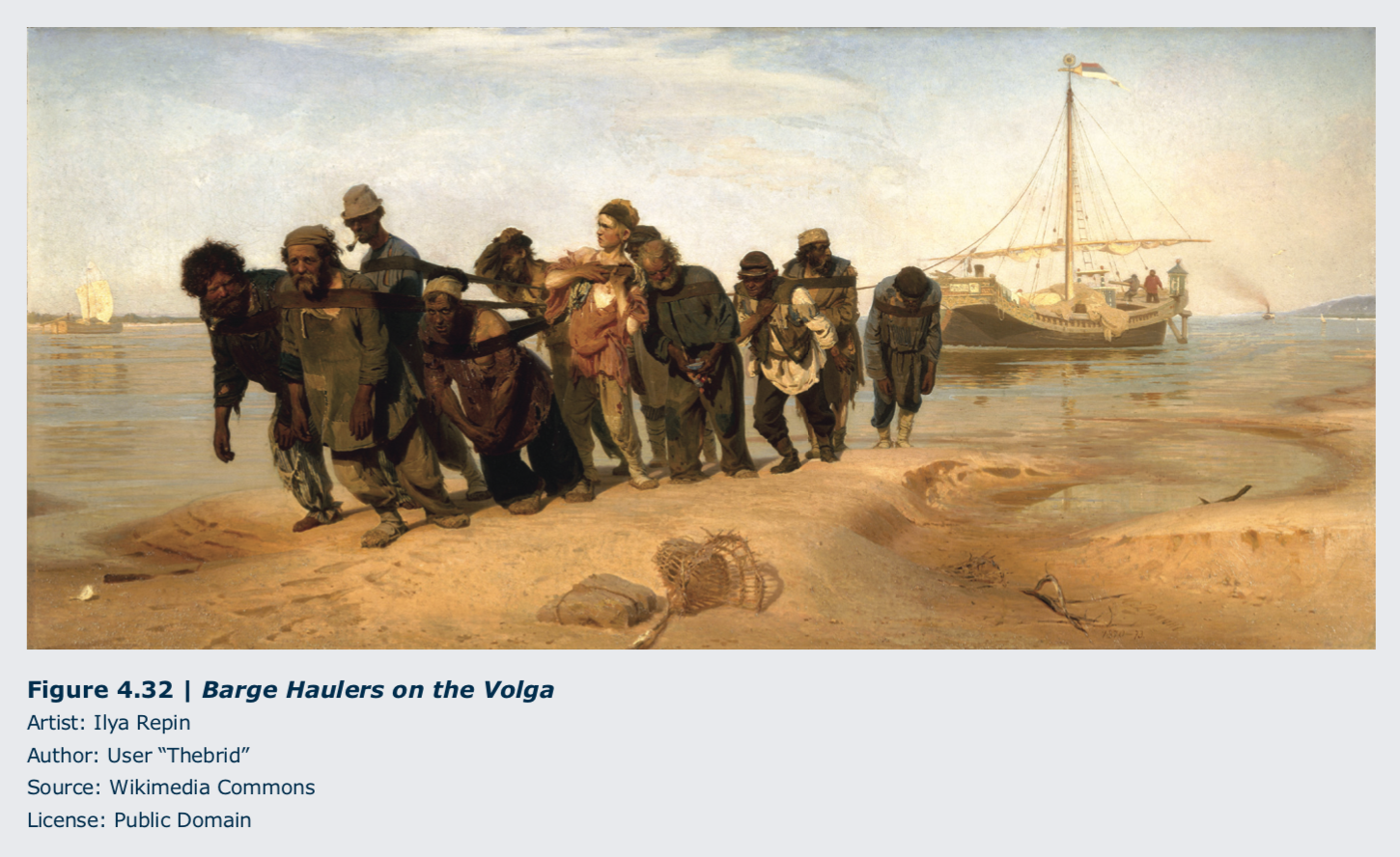

Such subject thing and approach to making art appeared in many different places throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Such art work invariably was associated with other signs of social modify and upheaval, ofttimes reflecting the lives and interests of the peasantry both rural and urban and highlighting the oppressive conditions of their lives. In Russia, amidst other places, the movement included a spirit of probing and of artists expressing the distinctive cultural characteristics and specific social is- sues of their countrymen. Ilya Repin (1844-1930, Russian federation), in Barge Haulers on the Volga, presented a realistic view of the arduous labor of men bringing the river barges to shore for unloading; the artist took great intendance to present each of them every bit an private to exist respected. (Effigy 4.32) He also defined them in terms of age, physique, stature, and ethnicity, conveying the group as a sort of cantankerous-section of Russian peasantry of the 24-hour interval.

In Germany, the influence of Courbet's Realism, coupled with study of portraits by Onetime Masters (European painters of renown c. 1200- 1800), appears in a written report by Wilhelm Leibl (1844-1900, Germany) called Three Women in the Church. (Figure 4.33) In this painting, the detail of the individual women is remarkable, delineating every bit it does their rustic costumes, their strongly individual characters, their large work- worn easily, and their other physical features. Leibl had rendered these peasants with realistic attention to the effects of their hard life at their unlike ages, while conveying a nifty sense of respect for their traditions of family and faith. He sought to counter the legacy of glorified German history and myth with unflinching views of the ordinary people he knew.

In Germany, the influence of Courbet's Realism, coupled with study of portraits by Onetime Masters (European painters of renown c. 1200- 1800), appears in a written report by Wilhelm Leibl (1844-1900, Germany) called Three Women in the Church. (Figure 4.33) In this painting, the detail of the individual women is remarkable, delineating every bit it does their rustic costumes, their strongly individual characters, their large work- worn easily, and their other physical features. Leibl had rendered these peasants with realistic attention to the effects of their hard life at their unlike ages, while conveying a nifty sense of respect for their traditions of family and faith. He sought to counter the legacy of glorified German history and myth with unflinching views of the ordinary people he knew.

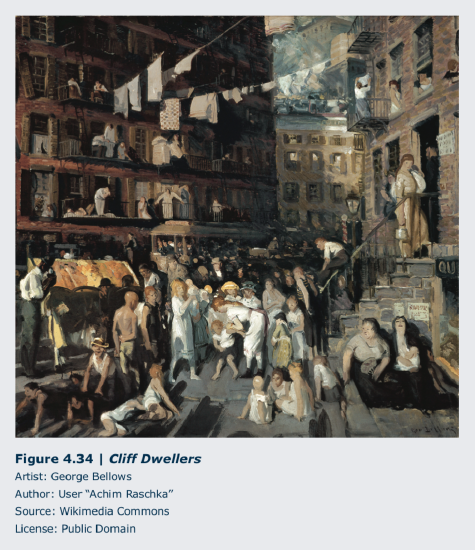

Stylistic components of and ideas behind Realism were too used past American artists, notably in the early on decades of the twentieth century, when the crowded urban centers fostered harsh living conditions for the poor working class citizens. I of import group within that stylistic movement, known every bit the Ashcan School, included painters such George Bellows (1882-1925, U.s.), whose Cliff Dwellers shows the crowding and chaos in a Lower Eastward Side New York City neighborhood on a hot summertime twenty-four hour period. (Effigy 4.34)

These artists were often making commentary on the undesirable furnishings felt by newly arrived immigrants and the rural poor who had been lured into large metropolitan areas in hopes of better prosperity and lifestyle, specially as many remained on the lower rungs of the industrialized and commerce-oriented society. Again, the overall definition of form may be seen as naturalistic, but his efforts for realism led Bellows to a rather painterly, brushy arroyo that does not take definitively naturalistic particular throughout.

One further particular betoken needs to exist made about the idea of realism in art. It is a mistaken notion to believe that photographic works are inherently or necessarily more realistic than any other work because they record some authenticity. The artist who uses photography has equally ma- ny opportunities for choice equally one who works in any other medium and can make choices that alter that actuality or its appearance. The photographer selects the subject field matter so can choose viewpoint, lighting, compositional field, a multifariousness of photo processes and materials, and exposure time. The process of development and printing offers farther options for manipulating the imagery, and sometimes changes are made afterward the printing process is complete. There is not necessarily any more than "truth" or "realism" in a photo than in any other type of art.

One further particular betoken needs to exist made about the idea of realism in art. It is a mistaken notion to believe that photographic works are inherently or necessarily more realistic than any other work because they record some authenticity. The artist who uses photography has equally ma- ny opportunities for choice equally one who works in any other medium and can make choices that alter that actuality or its appearance. The photographer selects the subject field matter so can choose viewpoint, lighting, compositional field, a multifariousness of photo processes and materials, and exposure time. The process of development and printing offers farther options for manipulating the imagery, and sometimes changes are made afterward the printing process is complete. There is not necessarily any more than "truth" or "realism" in a photo than in any other type of art.

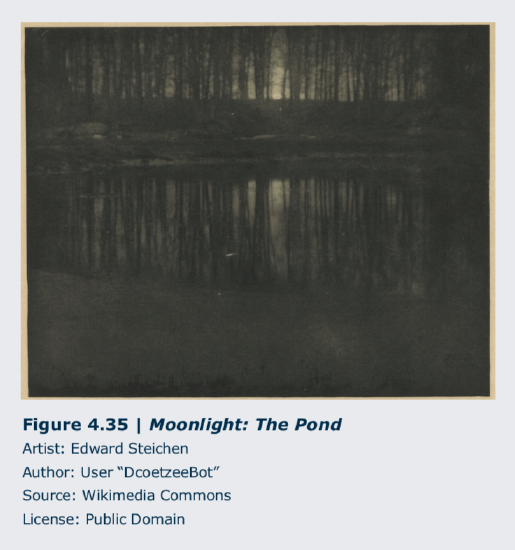

For example, in the works of some photographers such as Edward Steichen (1879- 1973, Grand duchy of luxembourg, lived USA) and Lucas Samaras (b. 1936, Hellenic republic, lives Us) we come across that the artists have manipulated the photographs to alter their appearances. Steichen used layers of gum bichromate to add color and to create a sense of hazy temper for a mysterious nocturnal landscape. (Figure 4.35) Samaras, on the other hand, created a type of photography he chosen Photo-Transformation by using his fingers and a stylus to move and smear the dyes of a Polaroid impress while still moisture. (Photo-Transformation, Lucas Samaras: http://www.metmuseum.org/fine art/collection/ search/265049) Leaving the protruding hand untouched, Samaras altered the spatial relationships in his photo by blurring the surrounding imagery, including his own face, which became quite indistinct in the procedure. The stages of creating photographs offer innumerable opportunities for altering the imagery from its "natural" appearances, while all the same often retaining the sense of "authenticity" of the photograph itself.

four.four.2.3 Expression(ism)

four.four.2.3 Expression(ism)

As we take seen, choices made to move away from naturalism tin can reflect both the culture at large and the bug with which artists concern themselves as they seek to express ideas and/or feelings of the moment. Expression has been sought for many purposes related to thought, belief, emotional impetus, and any man business organisation that might prompt the creation of artistic articulation, in its diverse forms and media. Often, though, the idea of expressionism in art is more narrowly used to define the thought of foregoing a measure of naturalism in favor of the emotional content, emphasizing how the culture and the creative person felt virtually the subject matter. This may be used in the Westward or East.

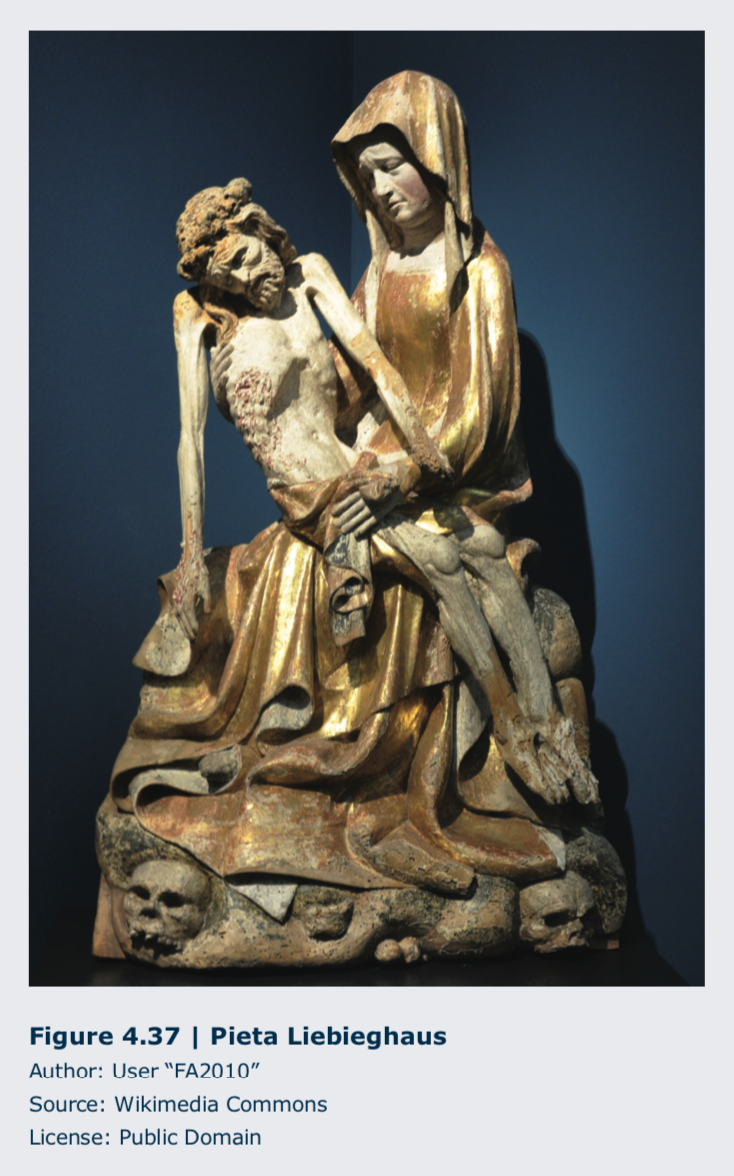

Examples are numerous in the illustrations of narratives, such as the Indian mythological story of the Hindu Goddess Durga, who dramatically slays the Buffalo Demon, using weapons borrowed from the male person gods. (Figure four.36) Such a story lends itself well to a dynamically expressive interpretation in art, as does the sort of devotional idea presented in the German language works called andachtsbilder , devotional images used to aid prayer, equally seen in Figure 4.37. These works were created on both small and large calibration to provoke contemplation of the sufferings of the Virgin Mary and Jesus Christ as prompted by the stories of the Passion of Christ. Such works were farther inspired by the relation of the holy figures' sufferings to the physical effects of the Black Plague, rampant from Asia to Europe during the fourteenth century.

A more than specific motion of Expressionism in Germany arose in the early on twentieth century to give artistic form to the emotional and societal reactions to unrest caused by political and cultural upheavals. Reflecting the desire for social reform that was part of Realism as well as the long history of expressiveness in High german art, the group was named the New Objectivity (Neue Sachlichkeit). In the aftermath of Earth State of war I (1914-1918), these artists presented harsh and piercing glimpses of the effects of the state of war's devastation on German society in the 1920s and of the ensuing societal unrest accompanying the emergence of the Nazis and the Third Reich in the 1930s. Artists such Max Beckmann (1844-1950, Federal republic of germany, Netherlands, U.s.) and George Grosz (1893-1959, Germany) used their craft to level harsh and cynical criticism against what they saw in the gild around them, at domicile and beyond Europe.

In Paris Order, Beckmann showed a group of businessmen, aristocrats, and intellectuals (many of whom emigrated to Paris to flee conditions at home) gathered for what ought to be an evening of social pleasantries, merely was instead one clearly pervaded by a sense of foreboding and gloom. (Paris Society, Max Breckmann: http:// world wide web.guggenheim.org/new-york/collections/ collection-online/artwork/503) The realism here shows the lack of connectedness amidst the partygoers, even to the extent that they apparently avoid or ignore one another, crowded as they are into an uncomfortable space. Beckmann himself, once a celebrated artist in Germany, became an object of censure and ridicule by the time of the Nazi regime, and his artwork is oft full of a sense of the malaise of the age.

Grosz, also despised past the Nazis, tended to make much more specific apply of his disquisitional realism, delineating especially harsh condemnations of the military and governmental establishments. For example, in The Hero, Grosz used graphic realism to convey his view of the anti-heroic handling of individuals—particularly Earth War I veterans—that he saw all around him. (The Hero, George Grosz: http://www.moma.org/collection_ge/ob...bject_id=72585) In the work of these 2 artists, nosotros tin note that the realistic approach sometimes moves away from potent natural- ism. The artists seem to have deliberately chosen to make their renditions somewhat abstracted and unrefined—even crude—for the sake of expressive accent.

four.four.two.4 Abstruse Expressionism

We examined differences betwixt representational and abstract art when we explored Van Doesburg's exploration of cows and the work of other artists who manipulated form past reducing its visual components or altering its advent and so that the form did non accommodate to the ways information technology might announced in nature. These artists chose to limit the degree to which they would carry the investigation of abstraction, opting to avert losing references that were more or less conspicuously recognizable.

In the eye of the twentieth century, based in New York City, a movement chosen Abstract Expressionism included works of drawing, painting, print, and sculpture that were focused on the physical backdrop of the medium used as opposed to pictorial narrative, although non all of them were without reference to the figure or the phenomenal earth altogether. In the piece of work Untitled of 1957 by Clyfford Nonetheless (1901-1980, United states of america), we see how the imagery can remind united states of america of a jagged crevice in a mount landscape, merely without definitive representation, and the artist himself denied that there was such a subject at that place. (PH-971, Clyfford Still: https://www.sfmoma.org/artwork/75.35)

Other artists associated with Abstract Expressionism used less sense of representation in their work. Included in the category were Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko (1903-1970, Republic of latvia, lived U.s.). (The Deep, Jackson Pollock: http://world wide web.wikiart.org/en/jackson-po.../the-deep-1953; No. 61 (Rust and Bluish), Marker Rothko: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:No_61_Mark_Rothko. jpg) Abstruse Expressionist artists were more than concerned with artistic process and formal means than with the creation of narrative pictures. In examining a small cross section of work by the Abstract Expressionist artists, nosotros can see that information technology may not exist appropriate, after all, to call this a stylistic category, as at that place is non really a stream of visual similarities among them; rather, they are characterized as much by their freedom from the constraints of stylistic rules and their lack of unifying visual features.

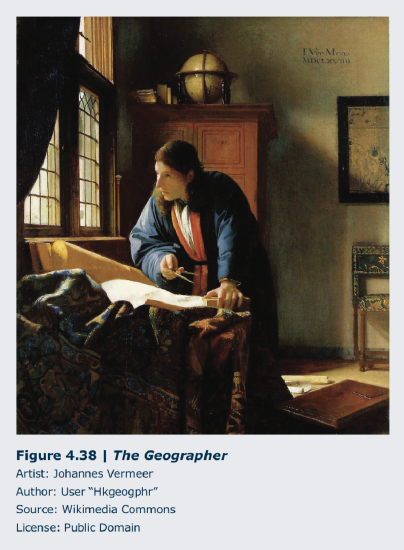

4.four.iii Individual Style

Johannes (or January) Vermeer lived in the seventeenth century, a fourth dimension of artistic flowering oft referred to as the Golden Age of Dutch art. During his lifetime, Vermeer was a painter of some renown in his hometown of Delft whose work was purchased by a small number of collectors. After his decease in 1675 at the age of 40-3, nevertheless, he and his piece of work were largely forgotten, in function because the few works he painted were in private collections and rarely seen. For example, Vermeer'due south painting The Ge ographer was in the hands of more than two-dozen private owners earlier it was sold to the Städel Museum (Städelsches Kun- stinstitut) in Frankfurt, Frg, in 1885. (Figure four.38) And, Vermeer himself was not "re-discovered" until 1860, when museum manager Gustav Waagen recognized a work attributed to another artist as a painting by Vermeer. Working with Waagen, art critic Théophile Thoré-Bürger published a catalogue raisonné, a detailed, comprehensive list of the artist's work, in 1866, launching Vermeer to ward the fame he and his thirty-four known paintings relish to this day.

Afterward such a long period of obscurity, it is all the more interesting that Vermeer is considered today to have such a distinctive style. Every bit in The Geographer, the corking majority of his works are set in a domestic interior, strongly lit by a multi-paned window to the left. Sunlight washes across the table at the window and the figure standing at that place, to the flooring and the wall backside. The objects in the room are both those commonly institute in a Dutch household of the day and specific to the occupation of a geographer, namely, the celestial world, charts, and compass the man holds. Vermeer achieved the luminosity of the scene, with small details warmly highlighted to a fine glow, by applying multiple layers of translucent glazes of paint. The palette of earth tones interspersed with the vivid blue of footing lapis lazuli and brilliant vermilion of powdered cinnabar provide a richness, clarity, and stillness that are distinctively Vermeer'southward, equally well.

Afterward such a long period of obscurity, it is all the more interesting that Vermeer is considered today to have such a distinctive style. Every bit in The Geographer, the corking majority of his works are set in a domestic interior, strongly lit by a multi-paned window to the left. Sunlight washes across the table at the window and the figure standing at that place, to the flooring and the wall backside. The objects in the room are both those commonly institute in a Dutch household of the day and specific to the occupation of a geographer, namely, the celestial world, charts, and compass the man holds. Vermeer achieved the luminosity of the scene, with small details warmly highlighted to a fine glow, by applying multiple layers of translucent glazes of paint. The palette of earth tones interspersed with the vivid blue of footing lapis lazuli and brilliant vermilion of powdered cinnabar provide a richness, clarity, and stillness that are distinctively Vermeer'southward, equally well.

The life and piece of work of Vincent van Gogh also provides united states of america with a good example to talk about the individual fashion of an artist. In improver to what can exist learned almost the artist through his drawings and paintings, the more than than 800 messages Van Gogh wrote to his brother, Theo, other family members, and friends, provide valuable information about his artistic intentions and thoughts about his fine art and life. After a childhood the artist described as troubled and lonely, he found happiness in 1869 at the age of xvi when he took a position with the fine art dealer Goupil & Cie, starting time in the Dutch urban center of The Hague and and so in London, England. Later leaving the house in 1876, nonetheless, he spent the next seven years in a serial of vocational and romantic pursuits that left Van Gogh disillusioned and adrift. In 1883, he began to pursue drawing and painting, for which he had shown promise equally a child. The two years he spent in Paris, 1886-1888, provided him with seemingly endless opportunities to study and grow as an artist. Overwhelmed by the stride of life there, withal, in 1888 he settled in Arles, a minor town in the south of French republic, where he spent the last two years of his life.

Largely based on the prolific artistic output during and biographical details almost those last two years, Van Gogh is well known every bit an emotionally troubled creative person who struggled artistically, financially, and socially. His piece of work from that period does not look like that of whatsoever of his contem- poraries, then we experience confident that his choice of field of study and technique reveals something personal and intimate rather than polished, distant, and conventional. (Figure 4.39) His swirling brush strokes and vivid colors seem to indicate the chaotic and emotionally turbulent life he was experi- encing. His choice of cypress trees as symbols of eternity reveal a concern with the spiritual that is well documented in his messages of the time. His passion, dedication to painting, and mayhap even a kind of desperation all seem to drive Van Gogh's individual stylistic approach.

Source: https://human.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Art/Book%3A_Introduction_to_Art_-_Design_Context_and_Meaning_(Sachant_et_al.)/04%3A_Describing_Art/4.04%3A_STYLES_OF_ART